I recently adventured into science journalism with a piece describing our recent article in PNAS detailing changes in forest structure over the 20th century. I talk about the use of the old data, and what the implications are for these changes. Check it out!

California’s majestic trees are declining — a harbinger of future forests

By Maggi Kelly, University of California, Berkeley

Scientists in my native state of California were handed a gift: a trove of detailed information about the state’s forests taken during the 1920s and 1930s and digitized over the past 15 years. When we compared this historical data – covering an area bigger than Great Britain – to current forests surveys, we found that California’s famed giant trees are suffering due to drier and warmer conditions.

This change to the forest landscape is important not only to the people of California. Large trees are huge sinks of carbon dioxide, provide habitat for many creatures and play a vital role in the water supply by, for example, providing catchment areas for snow. Forests that are denser with smaller trees are also more likely to burn.

Studying how the structure of forests is shifting over time provides us insight into how forests — a resource we depend on for many environmental and economic reasons — could change in a world of warmer temperatures.

Saved from destruction

Researchers from the University of California at Berkeley and Davis, the Department of Forest Management at the University of Montana, and the US Geological Survey’s California Water Science Center worked together on a paper on California’s forests published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The historical data for our study came from the Wieslander Vegetation Type Mapping (VTM) collection, which was created in the 1920s and 1930s. It’s been described in a 2000 paper as “the most important and comprehensive botanical map of a large area ever undertaken anywhere on the earth’s surface.”

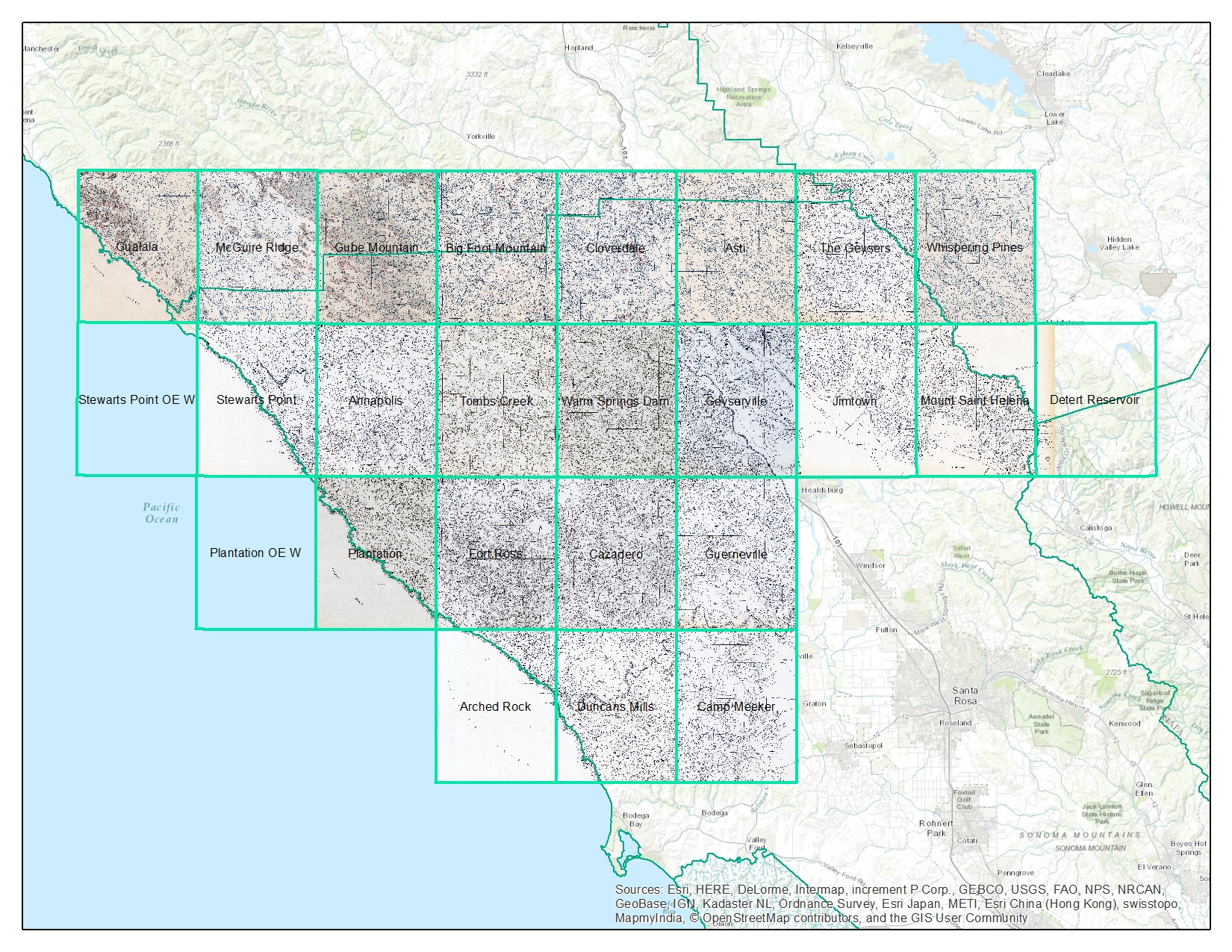

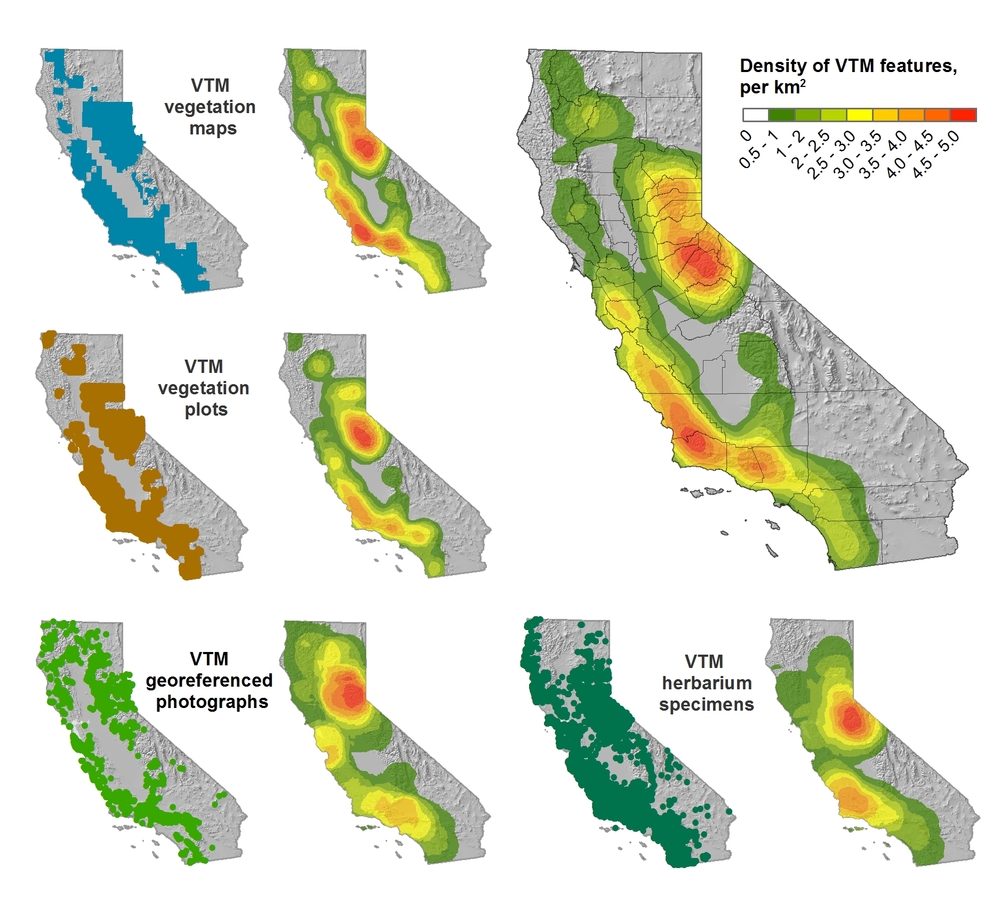

This botanical map was pioneered by Albert Wieslander, an employee of the Forest Service Forest and Range Experiment Station in Berkeley, California. The collection consists of 18,000 detailed vegetation plots, over 200 vegetation maps, 3,100 photographs and hundreds of plant specimens. Overall, the collection covers about 280,000 square kilometers, or just over a third of the state. Combined, the data created a detailed picture of the state’s vegetation in the early 20th century — an important marker ecologists today can use for comparison.

During the 2000s, several groups, including my lab, launched efforts to digitize the plot data, maps and photograph portions of the collection. There still are some missing pieces. Indeed, the journey from paper collection to digital data has been a long one, with several cases in which documents were nearly destroyed either intentionally or by accident. It’s a cautionary tale about the importance of rescued and shared historical data in ecological and geographical analysis.

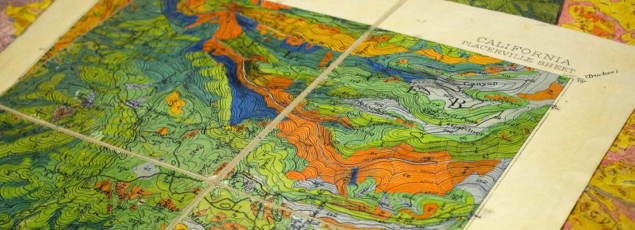

An example of one of the vegetation maps from the VTM collection. Shufei Lei, photographer

An example of one of the vegetation maps from the VTM collection. Shufei Lei, photographer

In our large trees study, we wanted to look at forest structure throughout the state by comparing the 1920s and 30s data with contemporary data collected through the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program. The FIA program is similar to the VTM project: Forest Service crews report on the species, size, and health of trees across all forest land ownerships. Our study was comprehensive, covering the five ecological regions of the state - over 120,000 square kilometers in total – and took into account land-management and land-use history.

Denser forests with more smaller trees

We found that statewide, tree density – or the number of trees in a given area – in forested regions increased by 30% between the two time periods and that forest biomass declined by 19%. This means that there are more smaller trees filling in the forest, while the number of large trees is shrinking. (A large tree was defined as having a diameter larger than 60 centimeters or two feet.)

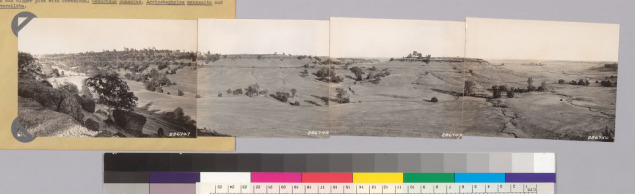

Wieslander’s photo of French Lake and English Mt. looking north, morphing into 2014 photo by Joyce Gross. Wieslander’s photo shows a large area of barren and semi-barren oak. University of California, Berkeley, CC BY

Wieslander’s photo of French Lake and English Mt. looking north, morphing into 2014 photo by Joyce Gross. Wieslander’s photo shows a large area of barren and semi-barren oak. University of California, Berkeley, CC BY

Also, we found that forest composition in California in the last century shifted toward increased dominance by oaks relative to pines, a pattern consistent with warming and increased water stress. It also fits the shifts in vegetation we can surmise from the paleorecord in California over the last 150,000 years.

Why this shift from fewer large trees to more smaller trees?

Water stress seems to be the best explanation for the pattern we observed. Water stress in a forest is caused by a combination of rising temperatures, which cause trees to lose more water to the air and to earlier melting of snowpacks, which reduces the amount of water available to trees. And indeed, large tree declines were more severe in areas experiencing greater increases in water deficit since the 1930s.

Large trees, in general, seem to be more vulnerable to water shortfalls. This might be because larger, taller trees have trouble getting water to the tops of the trees when water is short, a phenomenon being studied by many tree physiologists.

It might also be that these big trees – some likely 300 years old or more – grew up in a different, colder and moister climate. Regardless of the reasons for large tree decline, we likely can expect more water stress in California from rising global temperatures.

A different forest than what your grandparents saw

Apart from the fact that we tend to love and admire our emblematic large trees, they also serve very important roles in the forests. And changes to forest structure – a shift to fewer large trees and more smaller trees – are important for us to pay attention to.

Forests with large trees store more carbon; groups of larger trees provide preferential habitat for many species; forest structure impacts the way fires burn and impacts the way forests store and release water. These changes are a warning of possible changes to come. The loss of these trees, for example, would take away a massive carbon sink, change the way wildlife use these forests, and change the way they burn.

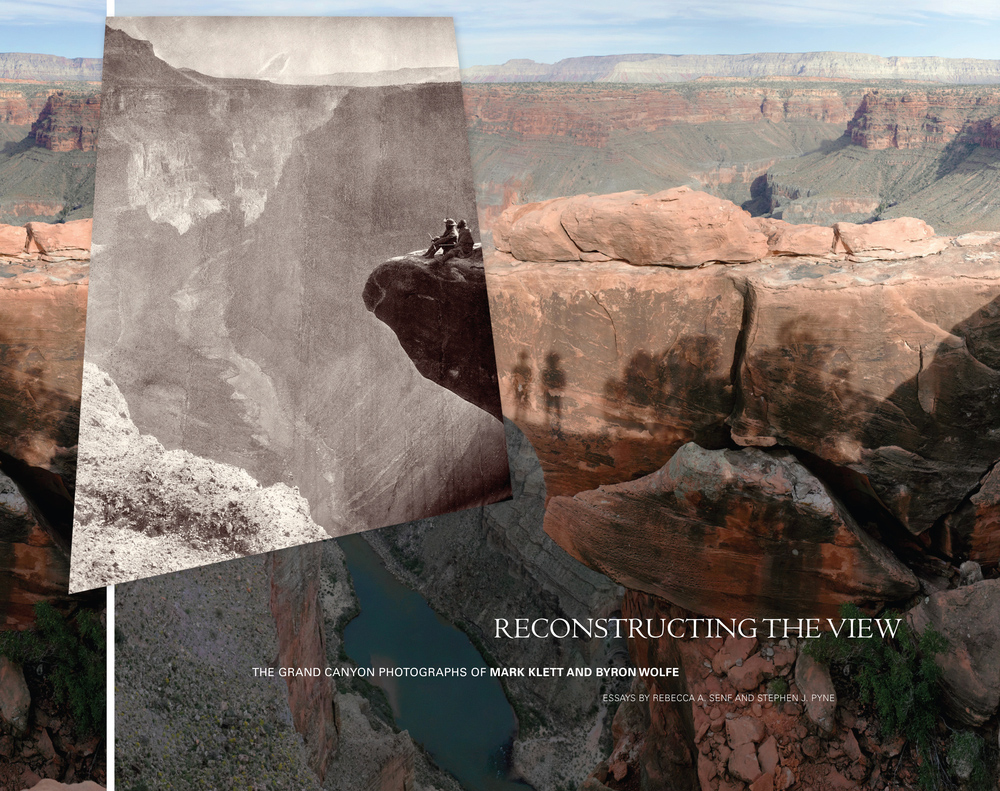

This photo was taken by Albert Wieslander in 1936 in a redwood grove in San Mateo County. The tree in the front has a diameter around 6 feet. Marian Koshland Biosciences Library

This photo was taken by Albert Wieslander in 1936 in a redwood grove in San Mateo County. The tree in the front has a diameter around 6 feet. Marian Koshland Biosciences Library

Finally, we would like to stress the importance of rescuing, curating and digitizing historic data. The changes we observed here, although large, did not happen over night – indeed, they really took two or three generations to occur.

Each generation perhaps sees the nature around them as the “normal.” Yet the forests of our grandparents and great-grandparents, observed by the Wieslander crews, were very different than ours today and they will be different again for our grandchildren. We need these historic data to document these changes and demonstrate the rate of change in the natural world.

Some key references:

Jepson, W. L., R. Beidleman, and B. Ertter. 2000. Willis Linn Jepson’s ‘‘Mapping in Forest Botany’’. Madroño 47:269–272.

Kelly, M., B. Allen-Diaz, and N. Kobzina. 2005. Digitization of a historic dataset: the Wieslander California vegetation type mapping project. Madroño 52(3):191-201

Wieslander, A. E. 1935. A vegetation type map of California. Madroño 2:140-144

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.